While climate change affects communities worldwide, First Nations peoples are bearing the brunt of environmental devastation at an alarming rate. The math is simple and brutal: Indigenous populations face displacement rates seven times higher than the global average. So much for caring about our “first peoples,” right?

Ice roads—once reliable lifelines for remote communities—are literally melting away. No roads means no food deliveries, no medical supplies, no mobility. Just air transport, which costs a fortune. Try paying $30 for a head of lettuce sometime. Food security? More like food anxiety.

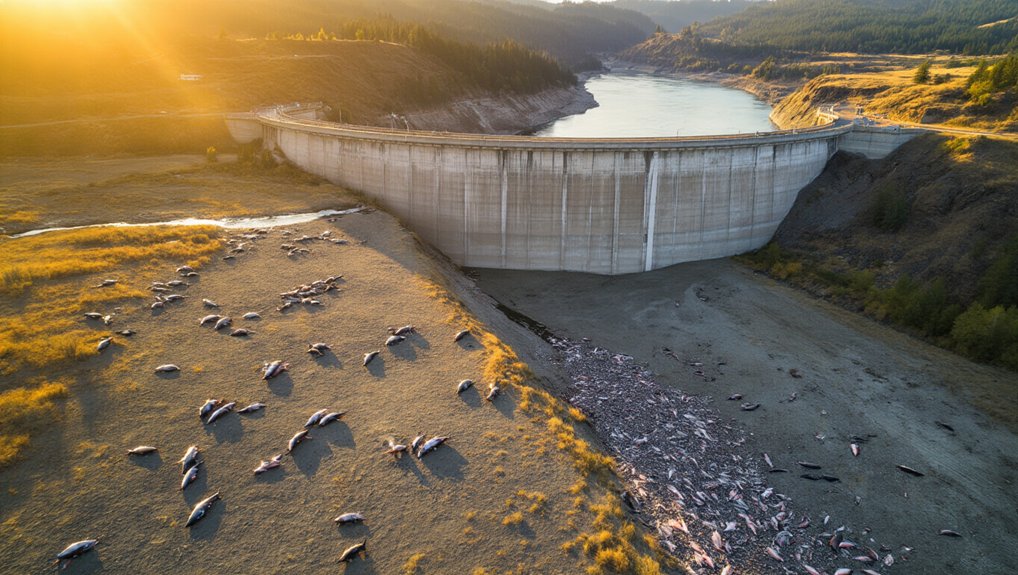

Traditional hunting and gathering patterns are collapsing as wildlife migration changes and plant populations dwindle. Caribou don’t exactly check the forecast before deciding their migration patterns. These aren’t just food sources disappearing—they’re entire cultural practices vanishing.

The irony stings: Indigenous peoples and local communities contribute least to greenhouse emissions yet suffer the most severe consequences. Local observations reveal tangible and nuanced impacts of climate change that instrumental measurements often fail to capture. Classic human history repeating itself. They’re watching ancestral lands disappear through permafrost melt, coastal erosion, and increasingly severe flooding. Once your land is underwater, no amount of adaptation helps.

Mental health crises are surging. Imagine watching your entire cultural identity—tied to specific places, animals, and seasonal rhythms—become obsolete in a single generation. Depression and trauma follow environmental loss like shadows.

Indigenous knowledge could help. Their hyperlocal environmental observations often spot climate changes before scientific instruments do. But who’s listening? Certainly not the systems that could use this information for effective adaptation strategies. Communities in Bangladesh have created floating vegetable gardens to adapt to increasing flood conditions, showing the innovation possible when traditional knowledge is valued. Unlike fossil fuels, geothermal energy sources could provide reliable power with minimal environmental impact for these vulnerable communities.

Water contamination from floods and thawing permafrost creates a perfect storm for waterborne diseases. Combined with crumbling infrastructure and healthcare access issues, remote communities face compounding health risks with few resources.

The cultural extinction threat is real. Languages die when communities scatter. Ceremonies lose meaning when their environmental contexts change. Traditional medicines disappear with changing ecosystems. This isn’t just climate change—it’s cultural erasure happening in real time.

References

- https://www.epa.gov/climateimpacts/climate-change-and-health-indigenous-populations

- https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/climate-change.html

- https://news.mongabay.com/2024/04/in-largest-ever-study-indigenous-and-local-communities-report-the-impacts-of-climate-change/

- https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/02/indigenous-challenges-displacement-climate-change/

- https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/10/21/my-fear-losing-everything/climate-crisis-and-first-nations-right-food-canada